Durpy, Haetae & Hojakdo

A Journey from K-pop Demon Hunters to Korean Folk Art

Recently, I watched K-pop Demon Hunters—a vivid, witty animation that brilliantly captures Korean aesthetics through a delightfully kitschy lens. Even as a Korean, I found myself laughing aloud at how cleverly it stitched together decades of K-pop nostalgia—from the ’90s to today—with quirky humor and vibrant visuals. One unforgettable scene features a fan wearing a duck hat, a detail that somehow felt both ridiculous and deeply endearing.

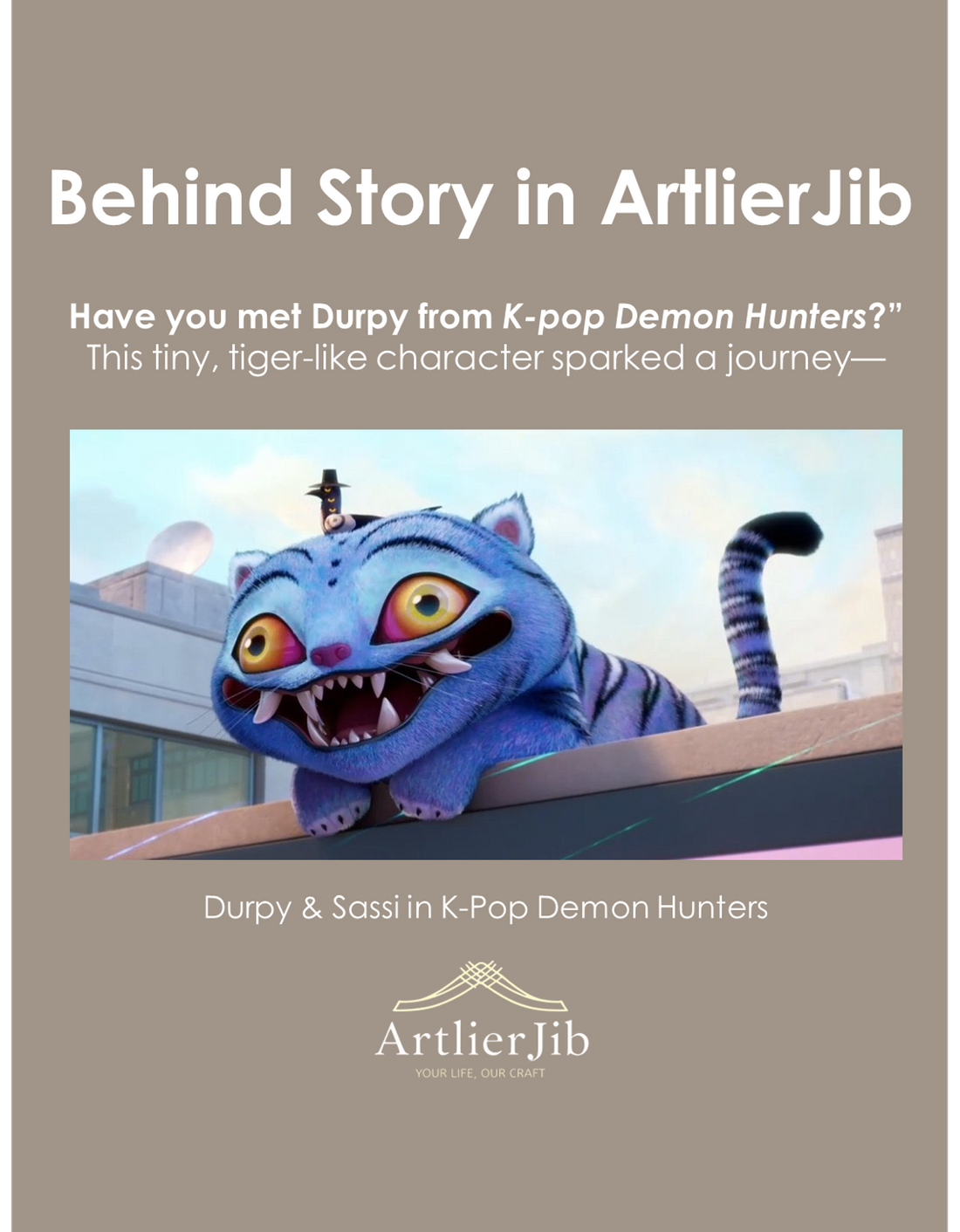

Ironically, I found the English voiceover far more immersive than the Korean dub. It gave the film a sharp edge, and brought unexpected nuance to characters like Durpy—a tiger-like creature who gently guides the heroine through a stone statue resembling a Haetae.

That moment stayed with me. Curious, I read through countless YouTube comments, where viewers debated whether Durpy was a lion, a tiger, or even a cat. It inspired me to revisit the story behind Haetae, a mythical guardian creature with deep roots in Korean and East Asian culture.

What Is a Haetae?

In Korean tradition, the Haetae (also spelled Haechi) is a mythical beast known for its ability to discern good from evil and drive away misfortune. During the Joseon Dynasty, it became a symbol of justice and integrity. The Office of Censors (Saheonbu), responsible for inspecting public officials, adopted the Haetae as its emblem. The Chief Censor even wore an official robe embroidered with a Haetae.

Today, you can still see Haetae statues standing guard outside Korea’s National Assembly and the Supreme Prosecutors’ Office—reminding those within to remain fair, alert, and committed to justice. At Gyeongbokgung Palace, a pair of Haetae statues stand near the entrance, believed to ward off fires and protect the capital, Seoul. Some say their placement was a response to geomantic concerns—Seoul being vulnerable to fire energy from Gwanaksan, a nearby mountain.

The Haetae in Chinese Mythology

The Haetae (獬豸, xiè zhì) also appears in Chinese folklore, where it’s described as a divine beast resembling a cow with a single long horn, bright eyes, a short, snail-like tail, and hooves like those of a sheep. It is said to live near water, possess a loyal nature, and instinctively attack those who are unjust in disputes. This innate sense of fairness made it a symbol of righteous governance in both ancient China and Korea.

Durpy & Sassi: A Quirky Duo with Deeper Roots

Durpy, with its fluffy stripes and solemn eyes, may look odd when paired with Sassi, the film’s heroine—especially when she’s wearing a gat (a traditional Korean hat) and accompanied by a magpie. Yet this unlikely combination has surprising historical resonance.

In late Joseon Dynasty folk paintings, a recurring theme known as Hojakdo (Tiger and Magpie) features these two creatures together. The magpie symbolizes good news, while the tiger—often drawn with exaggerated, almost comical expressions—represents authority or oppressive power. These paintings offered a playful yet sharp satire of ruling elites, allowing the common people to express both hope and critique through art.

Unlike the majestic tigers of Chinese imperial art, Korean tigers in Hojakdo are intentionally naive or foolish-looking, stared down or teased by cheeky magpies. It’s a charming, subversive tradition that highlights the Korean people’s unique sense of humor and resistance.

The Haetae Returns—In Clay

Artist Yujin Kim’s new Haetae teacup series revives this mythical guardian with a face that feels both solemn and approachable. Her interpretation captures the duality of the Haetae—its fierce appearance and benevolent purpose. It’s a reminder that strength can be gentle, and that even the most formidable forms can carry comfort and healing into our daily lives.

Guardians of Stillness

Bring a piece of mythical Korea into your everyday rituals. Shop the new Haetae teacup series by Yujin Kim